“Breaker of Chains,” written by showrunners David Benioff and Dan Weiss and directed by Alex Graves, stands as one of the single most controversial episodes in Game of Thrones’s entire run to date – a not-so-easy task, given the sheer amount of shocking material that has lodged the show so indelibly in the cultural consciousness. That controversy, of course, solely emanates from the instantly infamous rape scene between Queen Regent Cersei Lannister and her twin brother, Ser Jaime, in the Great Sept of Baelor, right next to where their son’s body lies in repose (not that the late King Joffrey Baratheon was the kind of gentlemen who demanded respect, even in death).

There has been a staggering array of work produced in response to this scene and its seemingly major deviation from George R.R. Martin’s source material (in the novels, it might behoove us to reiterate, Cersei clearly wants to have sex with her long-lost brother, even though she initially starts off by saying no), all of which has been confounded by a near-complete lack of response from either Weiss or Benioff. Parsing through the voluminous output both for and against the changes is neither welcome nor needed; viewers may just have to chalk it up to a mystery of the adaptation universe, a secret of the showrunners’ souls that they will more than likely take to their graves.

There has been a staggering array of work produced in response to this scene and its seemingly major deviation from George R.R. Martin’s source material (in the novels, it might behoove us to reiterate, Cersei clearly wants to have sex with her long-lost brother, even though she initially starts off by saying no), all of which has been confounded by a near-complete lack of response from either Weiss or Benioff. Parsing through the voluminous output both for and against the changes is neither welcome nor needed; viewers may just have to chalk it up to a mystery of the adaptation universe, a secret of the showrunners’ souls that they will more than likely take to their graves.

What is needed to be said regarding the deviation is much more straightforward, though no less confounding: does a viewer absolutely need to take the filmmakers’ intentions into account?

If the writers, director, and performers all approached the scene as being fundamentally consensual, as was Martin’s rendition, but had that intent obscured by what “defenders” claim is clumsy or otherwise sub-par cinematography and editing, should that factor into the emotional and intellectual responses that audiences have? Or does a piece of art, once it passes from its creators’ hands and enters into the annals of history, become divested from all the immediate circumstances of its inception?

What’s the most striking about rewatching the episode nearly two years later is how symbolic the rape scene has become for the series as a whole. The entire production is one vast web of conflicting – and conflicted – interpretations of characters (is Stannis Baratheon self-serving or ultimately self-sacrificial?) and ruminations on themes (how man is infinitely corruptible, whether it be the seduction of power that afflicts Stannis’s two late brothers or the all-consuming need for revenge, as Lord Petyr Baelish aptly illustrates). Is Lord Varys the Spider ultimately a hero attempting to save the realm from the ineptitude of would-be kings, or is he yet another cog in the game of thrones that endlessly, pointlessly plays out? Are the White Walkers, in this regard, animalistic savages or cultured warriors that know cancer when they see it?

There are many examples of this ambiguity and ambivalence that play out in “Breaker of Chains,” all of which are overshadowed by the Jaime-Cersei controversy: Sandor Clegane breaks guest right, just as Walder Frey did, but has a sense of fatalistic logic rather than a spurious sense of vengeance spurring his decision; Stannis Baratheon laments his inability to have Melisandre’s utilitarianism win out over Lord Davos Seaworth’s deontology; Daenerys Targaryen promises freedom to scores of slaves even though, given the sociopolitical realities of Meereen and Slaver’s Bay, it’s not destined to last. Hell, even Gilly misreads Sam Tarly’s intentions – he wants to protect her from the rabble that are his sworn brothers, but she thinks he’s just cruelly and casually casting her aside, like the burden that Craster must have seen her as. No one can seem to truly relate to anyone else in Game of Thrones; no one can ever seem to be able to know whether motivations can or should be divested from actions.

Speaking purely in terms of theme, what is actually the most loaded scene in the episode may very well be the Tywin-plays-the-tutor display that also happens directly in front of Joffrey’s still-warm corpse (one wonders where Jaime’s complete lack of respect or decorum comes from). Without a shred of sentimentality – actually, Lord Tywin openly insults Joffrey’s conduct as monarch right there, in front of Cersei and all the septons and septas – Tywin begins molding Tommen Baratheon into the kind of king that will be the most wise… which, of course, really means the most pliable, since it is Tywin himself who possesses a reservoir of infinite wisdom.

Tangled in this naked power play are the genuine lessons that the Hand of the King has to offer from history. And, indeed, he’s right – “A wise king knows what he knows and what he doesn’t,” and the same holds true for a wise citizen in the democratic nature of our modern world. The fact that such objective truth is lost under the weight of his own machinations – and in the death of a family member right in front of them – is simultaneously tragic and understandable, sacred and profane.

Of course, as the series has progressed since “Breaker of Chains,” Tommen has become the poster boy for the nature of power, the meaning of true leadership, and the political and psychological manipulation of rulers – in other words, the very premise of Benioff and Weiss’s show and Martin’s novels.

Introductions

There are a whole host of bit characters introduced in “Breaker of Chains” that, unfortunately, given the nature of their parts, ended up being exclusive to this one episode: the farmer and his daughter, Sally, that the Hound and Arya Stark come across in the riverlands, and the Champion of Meereen, who unfurls an impressively rude string of insults to Daenerys and her army.

There are a whole host of bit characters introduced in “Breaker of Chains” that, unfortunately, given the nature of their parts, ended up being exclusive to this one episode: the farmer and his daughter, Sally, that the Hound and Arya Stark come across in the riverlands, and the Champion of Meereen, who unfurls an impressively rude string of insults to Daenerys and her army.

But the main introductions here are, of course, Hizdahr zo Loraq, who would go on to become Dany’s betrothed (and the Sons of the Harpy’s punching bag), and Olly, who has his tragic origins as a wayward orphan be established here (thereby planting the seeds for yet more thematically grey material in the fifth season finale, “Mother’s Mercy”).

Deaths

Deaths

So long, Champion of Meereen! Essos was too cruel to thee. But no crueler than how Westeros – and a certain, scheming master of coin – treated Ser Dontos Hollard, the fat fool who was saved by Sansa early in the second season and then manipulated by Littlefinger to be her so-called knight in shining armor.

And, of course, we must also bid adieu to Olly’s family, who is all cut down by the advancing wildling party and is eaten by one very charming Styr. The north would never again be the same after this seemingly incidental scene, though no one – especially the audience – would know it for another season and a half.

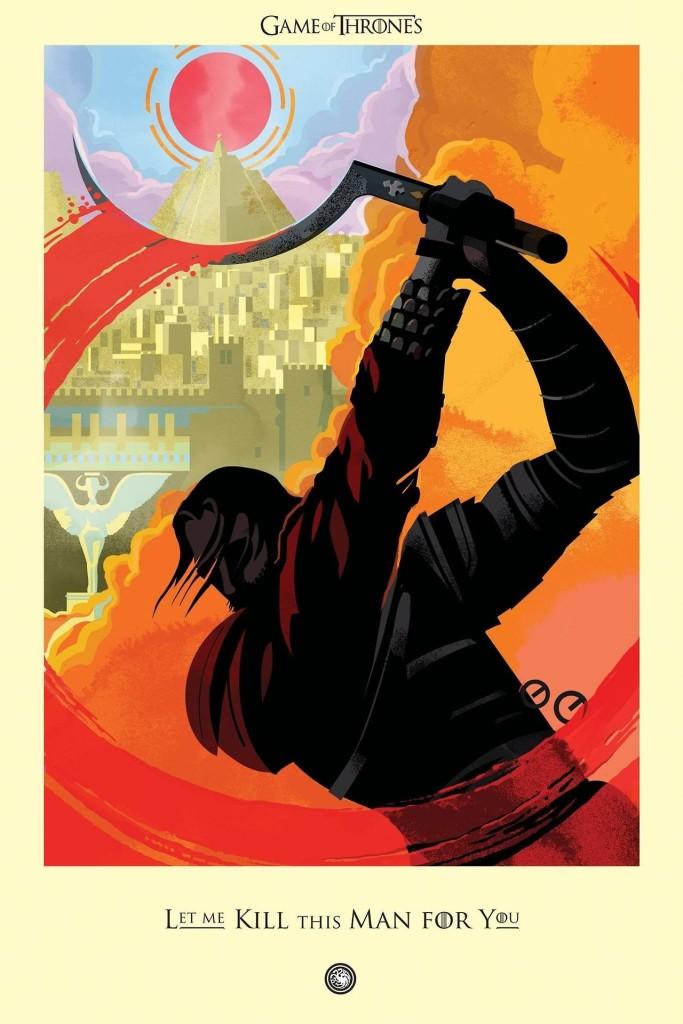

“Let me kill this man for you.” Daario fights the Champion of Meereen. Beautiful Death.

The post Game of Thrones Memory Lane 403: Breaker of Chains appeared first on Watchers on the Wall.

Via http://watchersonthewall.com

No comments:

Post a Comment